Photo Courtesy of Keith Carter

Albert Horton Foote Jr. was born on March 14, 1916, in the town of Wharton, Texas. He was only a year old when his parents moved to a house that his maternal grandparents had built for them on a lot that was basically his grandparents’ back yard. Although he left home at 16 to pursue his dream of becoming an actor, and lived most of his life in New York, both city and suburb, New Hampshire or California, it was the house he regarded as home for the next 90 years. It was on the front porch of that house that he also heard for the first time many of the stories he would later use as the basis for the more than 60 plays, movies and TV dramas that comprise the Foote literary canon.

When he was 12 years old, Foote informed his parents he wanted to be an actor when he grew up. Although dismayed by the decision, Foote’s father paid for him to attend the Pasadena Playhouse to study acting. After two years in Pasadena, Foote went to New York and continued his training with the Russian émigrés Tamara Daykarhanova, Vera Soloviova and Andrius Jilinsky while making the daily rounds of casting agents. Acting jobs, however, were few and far between and Foote joined a fledgling group formed by Mary Hunter called the American Actors Company. It was after performing an improvisation during a rehearsal there that Foote’s friend Agnes de Mille asked him if he had ever thought of writing. He went home that night and wrote a one-act play titled “Wharton Dance.” Hunter staged it in an evening of one-acts, but it was not until a year later that he followed up on the experience and, during a visit to his hometown, wrote his first full-length play, “Texas Town.” Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times reviewed that play and had great praise for the play, but little for the lead actor, which was Foote.

After Foote turned to writing full time, he discovered that starving writers can be just as hungry as starving actors, and he took a variety of jobs to support himself in New York. One of them was as a night manager in a bookstore in the old Penn Station. One day a young woman came in looking for a job. Her name was Lillian Vallish, and she later became Foote’s wife and lifelong best friend, lover, and literary soul mate. Refused service in World War II because of a hernia, Foote became immersed in the New York cultural scene. He became friends with another young writer named Tennessee Williams, and became involved in the new modern dance craze that was sweeping the country. He wrote narratives for several dancers, including de Mille, Martha Graham, Valerie Bettis and Jerome Robbins. He had one play on Broadway, “Only the Heart,” but it received only lukewarm reception. After the war, Foote and Lillian found the commercialism of the New York theater too restrictive and moved to Washington D.C. and for four years ran the theater at the King-Smith School.

Returning to New York about the time their first child, Barbara Hallie, was born, Foote took a job writing for the new medium called television. His first assignment was to write for the “Gabby Hayes Show,” but he was soon writing one-act TV dramas. The producer Fred Coe hired him to write 10 plays for television and one of them was “The Trip to Bountiful.” It was such a success on TV that Coe produced it on Broadway, and it became one of the most frequently produced plays in Foote’s canon. It later was made into a movie that won an Oscar for Geraldine Page and gained Foote his third Academy Award nomination for best screenplay.

During his time writing for the Golden Age of Television, Foote also adapted two stories by William Faulkner for the home screen, and those led to Foote being asked to undertake turning a novel by a new author into a screenplay. The novel was called “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and it would bring Foote his first Oscar.

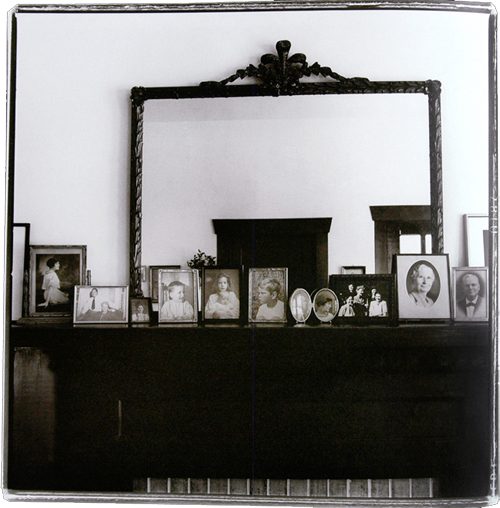

By the end of the 1960’s, however, tastes both in Hollywood and on Broadway changed, and Foote found little support for his plays. Foote and Lillian moved to New Hampshire and for a time Foote contemplated giving up writing. Both of his parents died within a year of each other, and in going through their letters and looking over their old photographs, an idea for a play came to Foote. Then another. And another. Before he was finished, Foote had written a nine-play cycle that he titled “The Orphans’ Home Cycle.”

During the two years he worked on the Cycle, Foote needed money, and at the suggestion of his agent, Lucy Kroll, he wrote an original screenplay. It was called “Tender Mercies,” and although studios were reluctant to back it, an independent producer finally got it made. Foote won his second Academy Award for the movie, and Robert Duvall, who acted in many Foote plays, movies and TV dramas and was a lifelong friend, won an Oscar for Best Actor.

Foote’s comeback in the theater began with small productions of individual plays of his “Orphans’ Home Cycle” at the H-B Studio in New York. Run by Uta Hagen and her husband, Herbert Berghof, the Studio was a home to aspiring actors and playwrights. After the tryouts at H-B, the plays were staged in Off Broadway theaters, and Frank Rich, then chief drama critics for the New York Times, gave them reviews that helped re-establish Foote’s reputation as one of America’s foremost writers. James Houghton’s Signature Theatre in New York devoted a season to Foote’s plays, and one of them, “The Young Man From Atlanta,” won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Independent film production was beginning to be recognized in the 1980’s, and Foote and Lillian formed a company that turned several of the plays from the Cycle into movies – “On Valentine’s Day,” “1918,” “Courtship,” “Lily Dale,” and later, “Convicts.” The years making those movies were among the happiest of Foote’s life, as they became a sort of family project. Lillian and three of their children – Hallie, who starred in three of the movies, Horton Jr. and Daisy, who has followed her father’s footsteps as a playwright, were all on the sets during the filming. Only Walter, Foote’s younger son who was away at college, was absent.

Michael Wilson, a young director in whom Foote found a innate understanding of his work, staged several other of his plays, including “The Carpetbagger’s Children,” “The Death of Papa,” “The Day Emily Married,” and “Dividing the Estate.” That last play transferred to Broadway and earned Foote a Tony nomination.

It was also Wilson who convinced Foote that the entire nine-play “Orphans’ Home Cycle” could be staged as a three-part theatrical event that would allow audiences to see all nine plays on three evenings, or in one all-day marathon. Foote spent the last months of his life adapting the plays into a production that Wilson presented at the Hartford Stage Company, of which he is artistic director, and later moved to the Signature Theatre in New York. Foote died on March 4, 2009, ten days short of his 93rd birthday. All the lights on Broadway dimmed that night as a tribute to his memory. For anyone who loved the theater, it is a memory kept alive nightly on stages across America.

—Wilborn Hampton